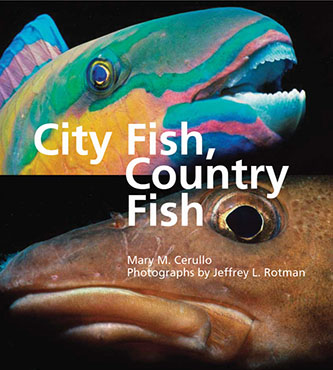

City Fish, Country Fish

Author Mary M. Cerullo Photographs by Jeffrey L. Rotman ISBN 9780884483236 Binding Trade Cloth Publisher Tilbury House Publishers Publication Date February 23, 2012 Size 229 x 254 mmSome people live in the country, close to the land, where they enjoy peace and quiet. Others live in high-rise apartments in the city and love the hustle and bustle of crowds and nonstop activity, both day and night. In the ocean, too, there are places that have some of the characteristics of "the country" or of "the city." Like the classic tale of The City Mouse and the Country Mouse, there are advantages and disadvantages to each habitat.

We'll compare how the fishes that live in tropical seas ("the city") and those that swim through cold oceans ("the country") meet the challenges and opportunities of their own ecosystems. We will examine how color, shape, and size, as well as behaviors and adaptations, help them survive in their particular habitat. We'll explore characteristics that make them different, as well as things that make them the same.

Mary Cerullo decided at thirteen that she ought to become an oceanographer. Although her career has always centered around the ocean, she discovered that she preferred exploring many different topics, which led her to teach and write about the ocean instead. She has written fourteen nonfiction books for children on ocean life. She likes to immerse herself in her topic, so a few years ago Mary accompanied Jeff on an underwater dive with ten Caribbean reef sharks. Mary's "day job" is associate director of Friends of Casco Bay, an environmental group in South Portland, Maine. For more about Mary: marymcerullo.com

Jeff Rotman started photographing ocean animals as a way to capture the attention of his middle-school students. As a reward when they finished their assignments, he would show them the slides he had taken underwater. He eventually gave up teaching to devote himself to underwater photography. His work has appeared in many popular magazines and books, both for children and adults. Some of his books include a coffee table book of his shark photos and a retrospective of his work. For more about Jeff: jeffrotman.com

Honor Book, Science K-6

—Society of School Librarians International

"Cerullo contrasts the lives of fish in tropical waters with those of their relatives in colder ocean regions. She explores differences in coloration, feeding habits, body shape, and survival techniques between the 'city fish' that inhabit coral reefs and 'swim in water as warm as a swimming pool' and the 'country fish' that swim through large underwater territories and cool waters. She also explains characteristics that all fish share and discusses how humans study the ocean. A final spread details the need to protect this important resource. Rotman's outstanding photos illuminate the underwater world with close-up views of tiny reef dwellers and unusual cold-water inhabitants such as the goosefish. Wider shots reveal the colorful bustle of reef life and schools of cold-water fish, including bluefin tuna. Design and layout reinforce the contrasts Cerullo identifies, making this a first-rate choice for browsers as well as students interested in ocean life."

—Starred Review in School Library Journal

"The familiar contrast between city and country is used to compare the teeming, colorful and diverse world of tropical fishes with the more uniformly colored, less varied and less crowded cold-water world.

"Cerullo, who used the city metaphor in her earlier Coral Reef (1995), organizes support for this extension in double-page spreads, contrasting the fish of warmer and cooler bioregions in various ways. She goes beyond number and density to consider such factors as size and shape, coloration, cooperation and specializations. Her interesting text sometimes sits on and sometimes adjoins Rotman's striking underwater photographs. Species are identified. The perspective often reflects the viewpoint of the photographer-diver—noting, for example, the different colors of the water. A section entitled 'How Humans Can Become Fish' describes scuba diving and includes an image of the photographer's wetsuit-clad son with a giant lobster. A final section connects this underwater world to our own. Words in italics are defined in a glossary, which includes important concepts (ecosystems, symbiosis, food web, tropical vs. temperate) and more specialized vocabulary (lateral line, barbel, phytoplankton, chromatophore). The short list of suggested further reading includes more of the author's writings and not much else, a disappointment in an otherwise informative title.

"This attractive new look at underwater life may inspire diving dreams for both city and country readers. (Nonfiction. 9-13)"

—Kirkus Reviews

"Mary Cerullo and Jeff Rotman have teamed up once again in this wondrous look into the ocean world. No matter where they might live, kids will be able to relate in fun and educational ways to fish living much like we do. Readers will return time and time again to read fun facts and enjoy the superb images of fish in their natural habitats, be they 'city' or 'country' dwellers."

—Ron Hirschi, fisheries biologist and author of more than fifty nature books for young readers, including Swimming with Humuhumu (a true city fish!)

"This unique approach to our underwater world provides a tantalizing introductory look at how fish live. Mary Cerullo's text is easy to understand, and Jeff Rotman's many photographs are impressive. The book is a worthwhile addition to any young reader's library."

—John Nuhn, Photography Director, National Wildlife

"With this fascinating book Cerullo and Rotman broaden the horizons of children while engendering a love and understanding of the sea. Their grasp of the oceans' complexity and their ability to distill and convey it to younger readers are special skills found only in talented educators. Rotman's dramatic images lure the reader, inciting curiosity and a lifetime of appreciation, seeding the next generation of conservationists and policymakers."

—Susan McElhinney, Photo Editor, Ranger Rick Magazine

Like the classic tale of The City Mouse and the Country Mouse, the fishes that live in cold "country" waters or "city" coral reefs are adapted to the challenges and opportunities of their own ecosystems. Tropical coral reefs offer many hiding places, but cold seas provide abundant food, more than enough to nourish huge schools of tuna, cod, and mackerel. The cold waters of temperate and frigid seas may look murky, but they aren't polluted. It's the rich sea soup of plankton that reduces visibility to a few feet under the water and makes it appear green above.

The fishes of cold waters live close to the earth, sport earth tones—tan, speckled, brown, or black—to match their surroundings, or are silvery to reflect back the light on the waves, and are robust and hardy for swimming long distances.

The animals on the reef have evolved complex strategies to compete for food and dwelling places in their city under the sea. They live in tight quarters at well-defined levels on the coral reef, like apartment dwellers in a high-rise complex. They are colorful, even flamboyant, in order to stand out in the crowd and attract a mate or defend their place on the reef. Even the smallest fish can be very territorial to protect its precious piece of real estate. A coral reef is active both day and night. There are even predators that prey on tired fish coming back to the reef at dawn and dusk.

City Fish, Country Fish will help inspire classroom conversations about:

Biodiversity and the amazing variety of fishes.

Comparing and contrasting ecosystems.

Adaptations for survival: for feeding, avoiding predators, and finding mates.

Threats to ocean ecosystems.

Underwater diving skills and technology.

Underwater photography.

Additional Picture Books

The Cod's Tale by Mark Kurlansky (G.P. Putnam's Sons, 2001)

The history of the fish that changed the world.

Coral Reef: A City That Never Sleeps by Mary M. Cerullo (Cobblehill, 1996)

The coral reef is active both day and night, and even as the "shifts" change, there are predators ready to pounce on weary commuters.

Hello, Fish! Visiting the Coral Reef by Sylvia A. Earle, with photographs by Wolcott Henry (National Geographic Society, 1999)

An introduction to some of the fishes that live on a coral reef for ages 4-8.

Sea Soup: Phytoplankton by Mary M. Cerullo (Tilbury House, 1999)

The plants that make up the bottom of the food web, as seen through a high-power microscope.

Sea Soup: Zooplankton by Mary M. Cerullo (Tilbury House, 2001)

Curious questions answered about the tiny animals at the bottom of the food web.

The Truth about Dangerous Marine Animals by Mary M. Cerullo (Chronicle, 2003)

As children read about notorious sea creatures, they learn that many of the most dangerous creatures in the ocean live in tropical waters.

Activity: Fishes Are All the Same—But Different

Adaptations are how plants and animals evolve to survive under certain conditions. City Fish, Country Fish provides lessons on how to make the most of the challenges and opportunities of one's surroundings. Read the story of The City Mouse and the Country Mouse and ask students to compare it to this book. What are the messages in both tales? Are they the same? Perhaps students can update the classic tale with a marine twist. They could choose one representative animal in each ecosystem, such as a cod and a long-nosed butterflyfish.

Activity: Fishes Are All Different—But the Same

No matter where they live, fishes also share common characteristics that make them FISH. They also make them much better adapted for living in the sea than humans are. Here are some questions that students could research, with helpful hints below:

What makes a fish a fish?

How do fish breathe?

How do fish find food? (senses)

How do fish use their fins?

How do fish stay afloat?

Are sharks fish?

How are fish different from mammals like us?

Fish have gills for extracting oxygen from the water. A lot of water has to be pumped over gills in order to get enough oxygen for a fish to breathe.

Their senses are well designed for navigating underwater. In addition to the senses of smell, sight, hearing, taste, and a lateral line, some fish, like salmon, can sense the magnetic field of the Earth, which helps them find their way back to the very place they were born years before.

Different fins are designed for swimming, turning, or staying upright in the water. Watch a fish in an aquarium sometime to see how it uses its fins. Normally, it uses its tail fin for propulsion, top and bottom fins for balance, and the side fins for turning and stopping. Some fishes, such as marlins and tuna, are such good swimmers that they can sprint through the water at speeds approaching 80 kilometers an hour (50 mph). If humans could only swim that fast!

Most fishes also have an organ called a swimbladder, which can inflate or deflate like a balloon to keep them at a certain level in the ocean. Sharks are fish, too, but they lack a swimbladder. Sharks' skeletons of cartilage are lighter than bone and help sharks to remain neutrally buoyant—able to float without sinking or rising. Sharks do have something other fishes don't: ampullae of Lorenzini, tiny sense organs embedded in their jaws and snouts that can pick up the faint electric pulses given off by all living things. This sense enables a shark to detect the beating heart of a flounder hiding under the sand.

Unless you have a fever, your body temperature remains the same—around 98.6°F (37°C)—whether it's hot or cold outside. Fishes, with the notable exception of great white sharks and tuna, are cold-blooded, which means their internal body temperature takes on the temperature of the water around them. Humans, dogs, dolphins, whales, and other mammals are warm-blooded, so their body temperature stays the same wherever they are. Coats, fur, and blubber help mammals stay warm in cold temperatures.

You'll find a useful pdf with the parts of a fish and diagram materials from the University of Maine at umma.umaine.edu/downloads/BonyFishAnatomy.pdf

Activity: Scientific Illustrator

Discuss the tasks of a scientific illustrator who must accurately portray every detail of an animal or plant specimen. Accepted practice for a scientific illustration of a fish is for the head to point to the left. Tell the students that they are going to become scientific illustrators who will reveal an entirely new species of fish to the world. Ask them to decide whether it will be a cold-water fish or a tropical fish.

Review some of the characteristics and adaptations of the fishes in each habitat: color patterns, shapes, and adaptations for protection, feeding, and finding a mate. Does this fish live near the bottom? Does it live in a school and have to travel far? Would it blend in with its surroundings or stand out from the background? Would its shape or color mimic seaweed or a rock? How might it protect itself? How does it capture prey—by luring it, chasing it, or surprising it? Once they have answered these questions, and others they might come up with, students can design their fish.

Activity: What's In a Name?

Have students refer to field guides of birds, fishes, etc., to see that each organism has both a scientific name and a common name. They also can go online to Fishes of the Gulf of Maine at http://gma.org/fogm/. Explain that the purpose of a scientific name is so that naturalists around the world will instantly recognize the plant or animal, whatever language they speak.

The system of scientific naming was created in the 1750s by a Swedish naturalist, Carl van Linne (which is usually Latinized to Carolus Linneas). Each organism is assigned a genus name, which is capitalized, and a species name in lower case. For example, the cod is Gadus callarias. When it is written, the scientific name is usually underlined or italicized. An organism's scientific name often describes some aspect of its appearance or behavior. The discoverers of new species sometimes include their own name in the scientific name. Invite the students to give their fish both a common name and a scientific name.

Activity: Fish Label

The most important signs in an aquarium are the labels that identify the animals in the tanks. Usually, each graphic label has an illustration or a photo, along with the scientific name and common name and some brief, interesting information about the creature.

Expand on the exercise above by asking students to come up with two or three sentences about their fish that visitors to an aquarium would find interesting or entertaining. For example, "A sea raven (Hemitripterus americanus) is a cold-water fish that can inflate its belly like a balloon, which may make it too big for a predator to swallow. It also makes grunting noises."

Activity: Fish Dishes

Visitors to tropical climates often dine on grouper, mahi mahi, and dolphin fish (NOT the mammal, a fish with the same name!). Sometimes these come with a side dish called ciguatera, which wasn't on the menu. Ciguatera [sig gwa-TER-ra] is a food poisoning you can get from eating reef fishes. Scientists think that small reef fishes feed on a special kind of phytoplankton. These tiny plants are poisonous to humans, but not to the fish. The small fish are eaten by larger, carnivorous fishes, which are then caught and served at local restaurants.

Soon after eating contaminated fish, a diner may experience terrible stomach cramps and vomiting. Some people say that their teeth feel as if they are falling out. Others feel a burning sensation when they touch something cold. There is no medical treatment; sufferers can only wait for the toxin to leave their system, which sometimes can take years. No one can predict which fish will be dangerous to eat because you can't taste, smell, or see if a fish is contaminated with ciguatera.

On the other hand, some people actually seek out poisonous fish to eat. It's found in the flesh and internal organs of about forty different kinds of pufferfish, which are called fugu in Japan. A talented fugu chef knows where the poison is concentrated in each kind of puffer, and he leaves just enough of it to give the diner a pleasant tingling sensation. If the chef leaves too much poison, it's likely to be the diner's last meal.

Hundreds of years before Europeans claimed to have discovered America, fishermen were crossing the Atlantic Ocean to capture huge schools of fish along the North American coast. Like most fishermen, they were reluctant to give away the location of their favorite fishing spots. By 1602, the secret was out when explorer Bartholomew Gosnold was so "pestered by cod" that he named an arm of land poking out into the ocean "Cape Cod." Later, Captain John Smith (of Pocahontas fame) used the name on a map of the New World.

If it weren't for cod, the Pilgrims might not have settled in Plymouth. They saw Captain Smith's map and, envisioning a future in fishing, established a settlement on Cape Cod in 1620. However, they apparently overlooked the fact that none of them knew how to fish or hunt. The Native Americans, seeing that the settlers were close to starving, showed them how to farm the land, and "how-to" instructions from Europe finally taught the colonists how to catch, dry, and salt the fish. Soon the colonists were providing salted cod, a tasty, long-lasting source of protein in a time before refrigeration, to all of Europe and the Caribbean. A wooden statue, known as "the Sacred Cod," hangs in the State House in Boston, Massachusetts, as a testament to the riches that cod fishing made for those early settlers and their descendants.

Cod and their relatives, pollock and haddock, have firm, tasty flesh. This white fish is sought after by diners, and so the fish are sought after by fishermen. Many cold-water fish travel in giant schools, which makes it possible—and profitable—for fishermen to capture thousands of fish at a time. They drag huge nets along the ocean floor. As the fleeing fish tire, they are swept into a smaller net at the back, appropriately called the "cod end."

Look at a map of the world and try to locate the prime fishing grounds listed below. How far are they from the Equator?

Georges Bank, off Massachusetts

Grand Banks, off Newfoundland

Southern Africa

North Sea

Iceland

Norway

Barents Sea

Bering Sea in the North Pacific

Gulf of Alaska

Coastal areas around Japan

Northeast Pacific

Alaskan coastal waters

Many of the most popular food fish have declined by 80 percent or more from over-fishing and habitat destruction. Find out more about the Sustainable Seafood movement. How could students promote eating varieties of seafood that aren't endangered?

Activity: Why is the Equator Warmer Than the Poles?

Shine a flashlight on a globe (or a round balloon). First shine the beam directly at the Equator, the line around the center of the Earth, then move the light straight up or down so it shines near a pole. Compare how concentrated the light beam is at the two different locations. Light spreads out over a larger area when it hits the North and South Poles. The light beam is concentrated when light ("the Sun") hits the Equator. Because the Sun provides not only light but heat to the Earth, the Equator heats up more than the poles. (Adapted from Stop Faking It! Air, Water, and Weather, by William C. Robertson, NSTA Press.)

Activity: Disappearing Colors

Being brightly colored is only useful if others can see you. Changes occur in the appearance of colors under water. For example, red objects frequently appear black under water. In the ocean, colors fade the deeper you go (and almost immediately in murky water). Colors are made up of different wavelengths of light that are absorbed at different depths. Many factors affect color: sunny day or cloudy day, high how the sun is in the sky (time of day), calm or choppy water, and water color, so these depths are just a guide:

Red is visible from 0' — 30'

Orange is visible from 0' — 45'

Yellow is visible from 0' — 60'

Green is visible from 0' — 80'

Blue is visible from 0' — 100'

Purple is visible from 0' — 120'

Ask students to make a mural of the ocean and show the depths at which different colors disappear. Discuss why underwater photographers need flashes and strobe lights even at shallow depths.